What is Bread? What are Cookies? How and Why I Tried Making My Own Recipes

This might seem like a big deviation from the other topics I've written about, but hear me out.

For a long time, baking seemed magical to me. I viewed recipes as something discovered by experts and then followed as law by the rest of us. Baking was an exercise in precision, but not creativity.

Watching The Great British Bake-Off– where season after season of amateurs seemed to create their own recipes or bake without them– nudged me towards a useful mindset shift: recipes aren't discovered, they're developed. That prompted me to try making my own.

Following instructions and baking something that I might have purchased was always satisfying and a little bit magical. Actually making the recipe itself is much slower and no longer magical, but it is even more rewarding and surprisingly accessible.

Ingredient Analysis

I still don't know what a professional version of this process might be, but I started by trying to understand the available levers. Primarily, what's the role of each ingredient, and how might different proportions impact the outcome?

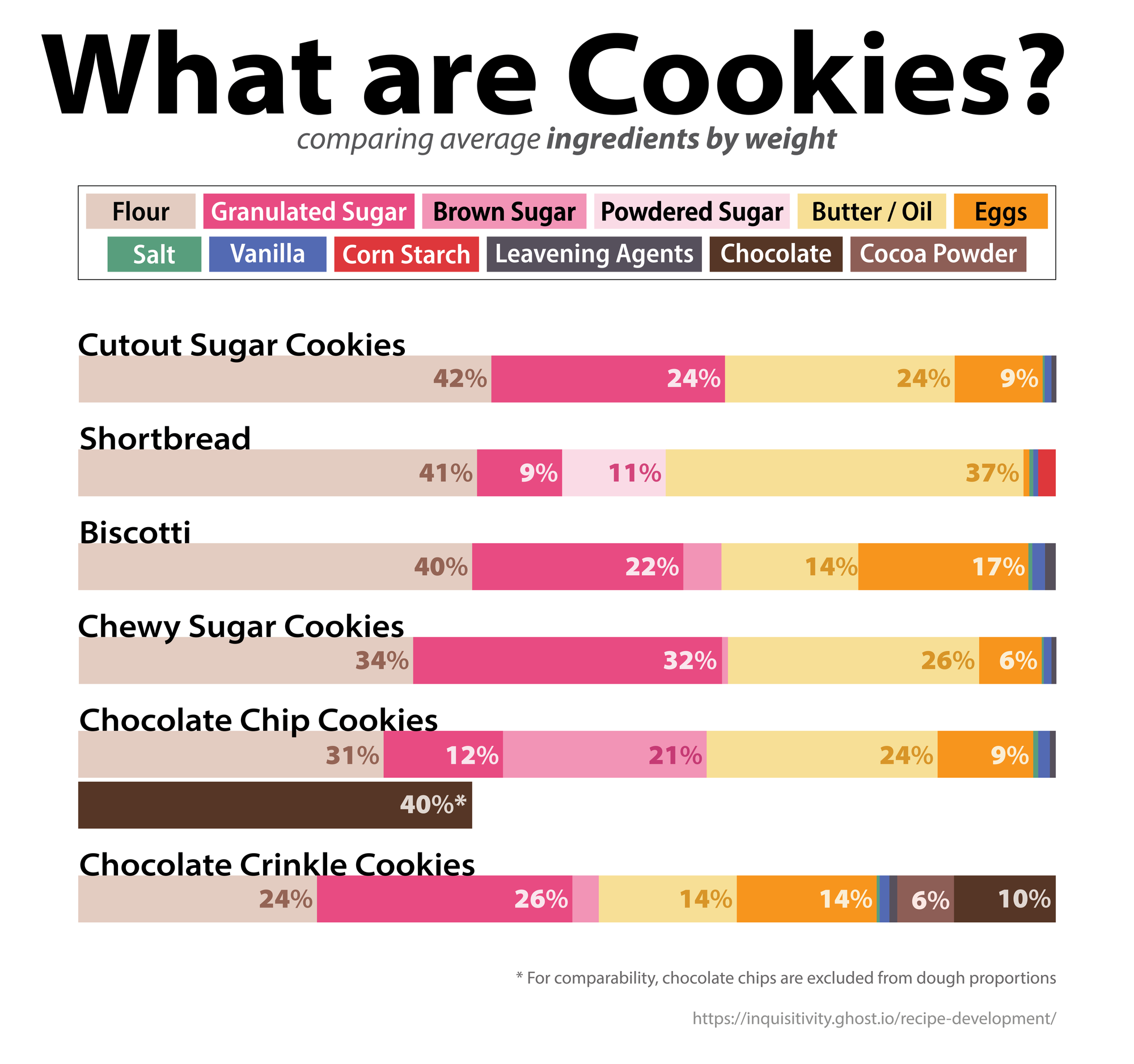

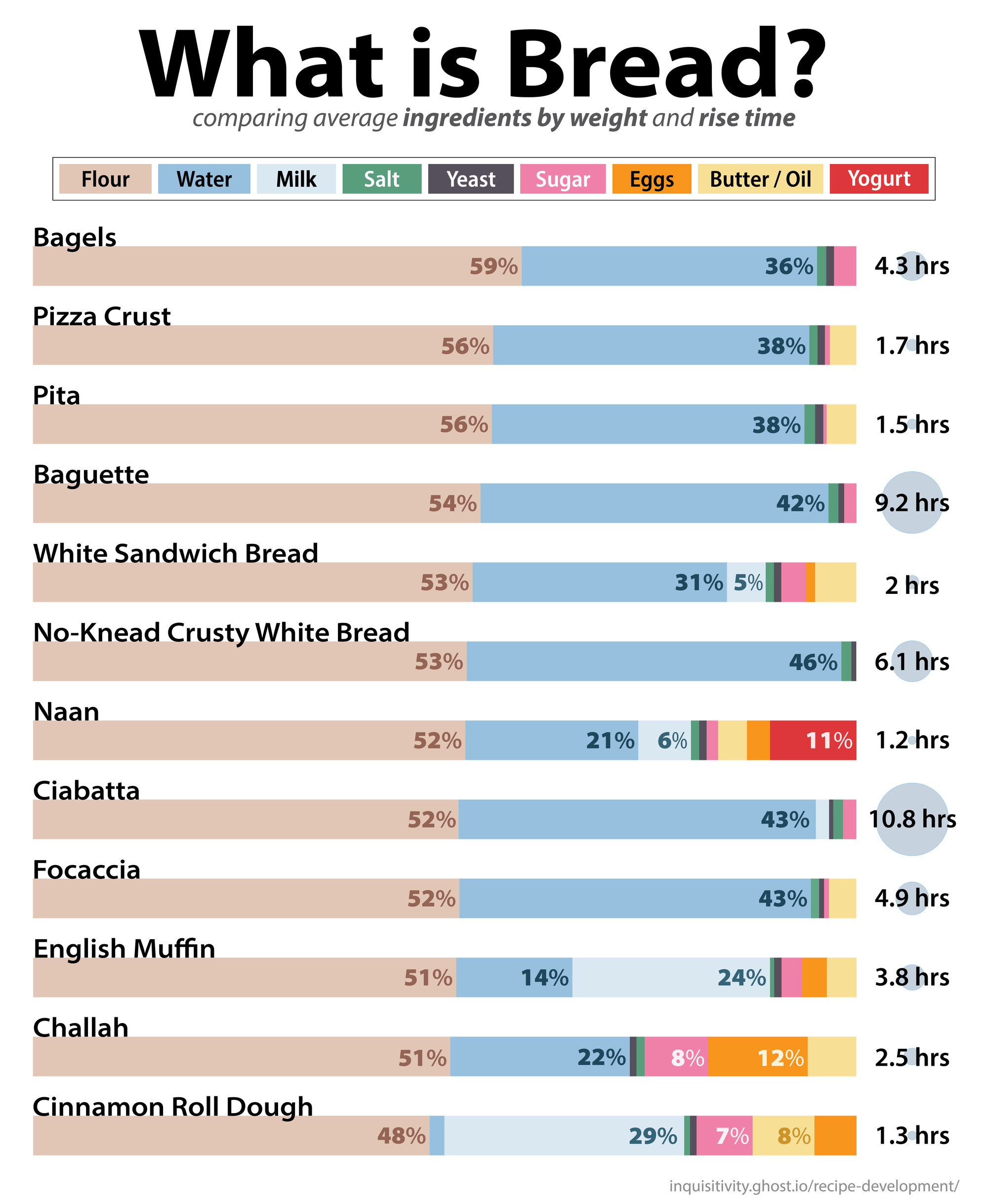

To answer those questions, I found the average ingredient proportions for 6 types of cookies and 12 types of bread [1]. This let me hypothesize about how I might achieve different results. For example, after considering the makeup of chocolate-chip and chewy-sugar cookies, I predicted that more sugar would yield a chewier cookie. Looking at shortbread, I thought that the large amount of butter and lack of eggs might be responsible for its crumbly texture. These aren't groundbreaking revelations, but having data to support them gave me the confidence to move away from existing recipes.

For the bread recipes, I also calculated the average minimum rise time. Altogether, this hinted at the texture that adding oil or milk might create, and it revealed an inverse relationship between yeast and rise time. But overall, my understanding still feels incomplete, perhaps because important technical variables– like kneading and shaping– aren't represented.

Recipe Iteration

To actually develop a recipe, I used this information to make a first guess at the right ingredient quantities. From there, I experimented with chill time, bake time, bake temperature, ingredient quality, and other specific techniques (browning butter for cookies, different kneading times for bread, etc.). After each attempt I identified what needed improvement, then made changes to get closer to the idea in my head.

My most successful attempts:

- "Optimized" Chocolate Chip Cookies: This approaches my idea of the perfect chocolate chip cookie.

- Frangipane Cookies: I've been eating a lot of frozen almond croissants lately. These cookies were inspired by the almond filling that spills out during baking.

- Corn Flake Cookies: A chewy, salty, corny, caramel-y cookie that I imagined and wanted to see if I could create.

- No-Knead Oat Ciabatta: Developed to avoid buying a whole bag of whole wheat flour.

I'd still like to improve these recipes, try new flavors, and learn more about ingredient substitutions. My process is not perfectly honed, and I'm not even suggesting that you try to replicate it. This is just an account of how I ventured into recipe development and my realization that it's really a series of surprisingly accessible steps.

Why is this useful or interesting?

I'm not an expert on recipe development, and I don't think it's something that everyone needs to do. I don't even expect this analysis to be directly interesting to a wide audience.

Instead, I'm sharing this because it helped me practice thinking for myself. There's nothing unique to baking that made this possible, but it is a constrained, low-stakes problem, which means that experiments are easier to run, results are easier to measure, iteration is faster, and emotional thinking is less likely to get in the way. Also, it's fun.

Curiosity is both a muscle to flex and a result of the confidence that your questions are answerable with effort. The world is full of things to be investigated, reasoned about, experimented on, and understood. It's not a set of opaque laws that only credentialed experts get to interpret. Recipe development is just one way to practice this mindset, and baking is only as important as you make it. But the mindset itself– inquisitivity, if you will– is indispensable.

Footnotes

[1] To compare ingredient quantities, I converted all ingredient quantities to weight, using an iOS application called First Proof (yes, I made this application, and yes, I'm plugging it shamelessly, but I do think it's genuinely useful). Then I calculated the ingredient proportions per recipe and averaged those.