What Should I Do About Climate Change?

There's no shortage of speculation on this question. On one end of the spectrum, we're being sold countless new products to offset tiny amounts of trash (straws, tea bags, etc.). On the other, we’re instructed that nothing short of dismantling capitalism will suffice. I’m skeptical of both extremes, but a pervasive lack of data or context makes it difficult to reach a conclusion with much confidence.

Most popular suggestions seem directionally good, but they’re almost impossible to prioritize or contextualize. If we can’t meaningfully compare “turning off the lights” with “taking shorter showers”, and if we don't understand our total environmental impact, then our actions become some kind of guilt-assuaging exercise, rather than an evidence-based response. Given the magnitude of this problem- and the many other problems we face- we can’t afford to waste our time, effort, money, or political-will on Green Theater [1].

Should we focus on individual action at all?

Calls for individual action are often met with claims that climate change was really caused by corporations and that consumers shouldn't be blamed for their actions. If so, is there anything individuals can do?

These debates often cite the popular finding that just 100 companies are responsible for 71% of emissions. But that's a little misleading. Most of the top polluters are government entities or multinational oil and gas companies, and 90% of those emissions came from the downstream use of fuels they sold to individuals and smaller companies. Is it really accurate to blame ExxonMobil for the emissions produced by my car, just because it’s fueled by their gasoline?

Plus, by design, the study being cited only considers emissions from fossil fuels. Other sources, such as cement production and landfill gases, may be distributed differently.

It's certainly fair to say that these corporations could have outsized power in leading a transition away from fossil fuels, but it doesn’t imply that they're solely to blame. Ultimately, corporations exist to sell things to consumers, and our huge appetite for cheap energy shaped these companies into what they are today.

Of course, corporations have also tried to unfairly shirk responsibility here. For example, they've unfairly perpetuated the myths that if consumers simply limited their excesses or recycled enough then things wouldn't be so bad.

It’s tempting to simplify big problems by focusing blame, but in a complex and interconnected world, there's no easy scapegoat. Stalling climate change will absolutely require corporate and government action, but it will also require pressure from individual consumers, especially those with the luxury of choice.

What's going on? What needs to be done?

Climate change is caused by greenhouse gas emissions, but it's often conflated with other environmental concerns, such as plastic pollution in the oceans. While all environmental issues are probably somewhat related, it's important to differentiate between them. Plastic pollution in the oceans is a serious problem, but plastic in landfills is not [2]. To avoid catastrophic temperature increases, we’ll need to reduce our CO2 emissions from 50-billion tons per year to zero. Accomplishing that will require focus.

In his recent book, How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, Bill Gates points out that we won’t reach zero-emissions solely by scaling back human consumption. For all the cancelled flights, avoided commutes, and economic devastation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, global emissions in 2020 only decreased by about 5%. The cost of scaling back does not seem scalable.

Gates's plan focuses instead on replacing fossil fuels with clean electricity everywhere we can. This will require updating a lot of non-electric infrastructure (cars, furnaces, etc.), then dramatically scaling up clean energy production to meet the new demands. For everything that’s not easily electrified (airplanes, cement, etc.), we’d rely on some combination of carbon capture and new technologies. Optimistically, he asserts that there's just enough time to implement the necessary changes, but that we can't waste time on short term fixes that could stall development.

Some activists disagree about the extent to which we should rely on technology to save us. They argue that we all have an immediate responsibility to scale back our consumption, because even if innovation gets us to carbon-zero eventually, the damage done in the meantime will be far too costly.

These models differ on the appropriate balance of environmental vs. economic risk, the prioritization of immediate vs. long term changes, and the likelihood of avoiding catastrophe. There's real debate as to the optimal approach, but not the necessity of action or the ultimate goals. Even without a resolution, individuals who want to help can incorporate some principles of both as they decide what to do.

So what should I do?

Accelerate electrification

Clean electricity is our most promising tool, but widespread use is limited by infrastructure and consistency. The sun sets, the wind slows, and we currently lack the battery technology to bridge those gaps affordably. Households can ease availability constraints by reducing consumption and coordinating with periods of availability (i.e. daytime). And we can assist the infrastructure change by switching to heat pumps, electric cars, and electric stoves as it’s feasible [3]. Individual consumers may not have complete control over the shift to clean electricity, but we can extend the runway and make existing solutions viable sooner.

Shrink your carbon footprint

Ultimately, innovation, policy change, and infrastructure replacement on the scale required will be slow, and global temperatures are already rising. So while energy conservation alone won’t be enough, it could buy us valuable time in the race against irreversible damage.

Decreasing consumption usually comes with a cost- in the form of time, money, effort, enjoyment, or social capital. Taking public transportation requires more time and effort than driving. Skipping a cruise with friends costs enjoyment and social capital. Because the idiosyncratic costs and benefits of our actions vary so widely, it's critical that we prioritize them thoughtfully.

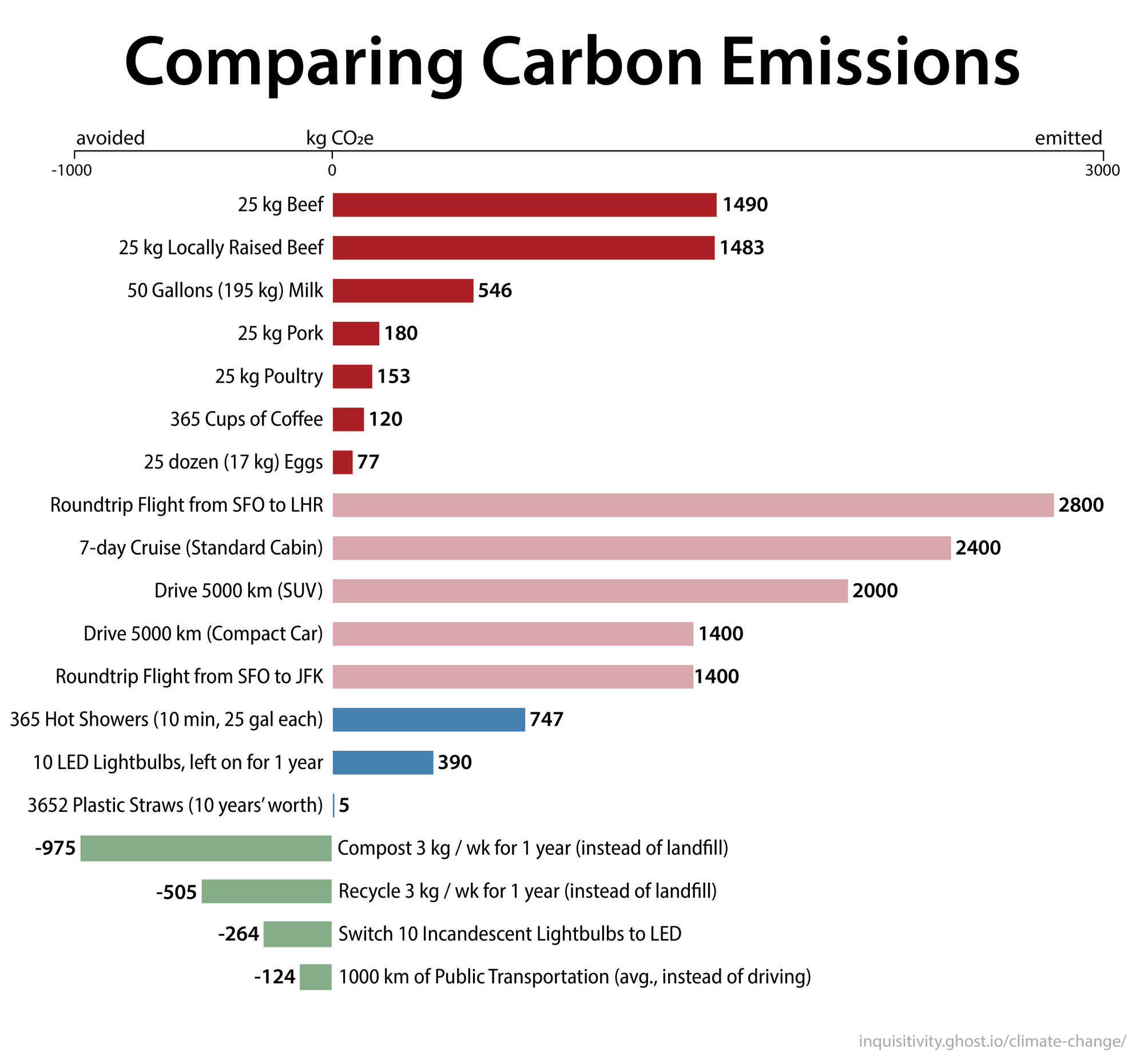

I've quantified the emissions (avoided or emitted) of some individual actions, all in terms of kg CO2-equivalents. For context, the United States' emissions in 2019 were equal to 16,060 kg of CO2 per person. More detailed data, sources, and calculations are documented here.

Emissions from cruises and air travel add up quickly. Just one roundtrip flight from London to San Francisco would equal 17% of the average American's annual emissions. But the average American doesn't fly to London each year. Those of us who are lucky enough to fly often should not ignore our disproportionate environmental impact. We may diligently avoid hamburgers and single-use plastics, but those benefits are quickly overtaken by a few flights, and we should not delude ourselves into thinking otherwise.

Plastic straws are on the other end of the efficacy spectrum. For all the attention they receive, the benefits of avoiding them are tiny. Skipping just one serving of beef could offset a decade of straw use. If you live in a developed country and dispose of your straws properly, they're nearly harmless.

It's also popular to emphasize the environmental costs of animal products, but we should note that beef is by far the worst contributor. This is because cows [4] excrete methane, an extremely potent greenhouse gas, during digestion. They also require a lot of land, which can lead to deforestation or high opportunity costs. If a vegan or vegetarian diet isn’t practical for you, replacing even a portion of your beef consumption with eggs or chicken is still an effective way to shrink your carbon footprint [5].

If you’re not able to make dietary changes, just addressing food waste and disposal can make a big difference. About a third of the food produced in the United States goes to waste. If that food is sent to a landfill, it will decompose in a low-oxygen environment and release the equivalent of six times its weight in CO2.

These high emissions make composting a very effective tool. Composted food will decompose in an oxygen-rich environment and only release the CO2 it captured while growing. Even better, finished compost can be used to grow crops and sequester additional carbon in the soil.

Recycling is often heralded as a key component of fighting climate change. It is useful, but only when things actually get recycled. Aluminum, glass, and paper are great candidates, but as recent criticism has revealed, some types of plastic (especially #3-7) are so hard to recycle that they often end up in landfills, sometimes after being shipped across the world. And the plastics that do get recycled can only go through the process a few times. There are situations where plastic is genuinely less harmful for the environment- it's lightweight, durable, cheap, and great for preserving food- but we've been sold a story about how easily it can be recycled that just isn't true. Recycling Is a great tool, but throwing something in a blue bin doesn't absolve us of responsibility.

While this analysis isn't comprehensive, it does show how much your impact can vary depending on your approach. Shrinking our personal carbon footprints is the most direct form of impact that we have, so we should do it in an informed, effective way. Then we should look up to think about how else we might have an impact.

Influence corporations and elected officials

Governments have concentrated power to incentivize electrification, regulate the energy economy, and invest in research. Individuals who live in democracies should not neglect their ability to sway elected officials through protest, voting, donation, and outreach. This is especially important when considering important but potentially unpopular interventions, such as spending taxpayer money on risky research investments or imposing a carbon tax.

Likewise, corporations will respond if consumers collectively signal support and demand for environmentally friendly practices. For example, many energy providers have programs where you can pay a modest fee to help fund renewable energy generation. Opting into these programs signals that there is demand for clean electricity, even if it costs slightly more. Not everyone has this luxury of choice, but those who do should consider the impact of their purchasing decisions.

Applied well, these interventions can magnify effective efforts. Applied poorly, they can amplify Green Theater and reward performative changes. The ripple effects of our behavior are inherently hard to quantify, but they underscore the importance of clear, accurate prioritization.

Accelerate innovation

In addition to government and corporate intervention, climate change solutions will also require technological advancements. This research is likely to be funded mostly by governments, so influencing elected officials is one good way to push it forward.

If you have specialized skills that could be used to actually do the needed research, then applying them could be extremely helpful. If you have money to donate and a deep understanding of the space, you could support promising research directly, but it should be weighed carefully against other charitable efforts and climate change interventions.

What will I do?

- Fly less. I'll try to minimize my flights by taking fewer, longer trips; and I'll consider distance when choosing destinations. I also realize that flying is a luxury, and I'll consider purchasing carbon offsets when I do so [6].

- Eat less beef. Before this research, I knew that animal products were high emitters, but I didn't realize the disproportionate costs of eating beef. When I do eat animal products, I'll opt for poultry or eggs more often.

- Heat my house more efficiently, using more renewable energy. Even in temperate San Francisco, my heating bills were pretty high this winter. I set my thermostat to a lower temperature and improved insulation. I'll also enroll in our local solar energy program.

- Compost. I'm lucky to live in a city that has curbside compost collection. Understanding the high environmental cost of landfilled food has prompted me to compost more diligently and to encourage my roommates to do the same.

- Don't console myself by avoiding small amounts of plastic. Remembering to bring my reusable bottle to the airport does basically nothing to offset a flight. And continuously buying more reusable products may do more harm than good. At the very least, be honest with myself about that.

Because I don't drive or own a house, I'm not able to buy a heat pump or an electric car, but I'd strongly consider them if I did.

Why Should you Care?

This focus on prioritization may seem unnecessary. If something is good for the environment, isn't it worth doing?

Failure to prioritize our efforts will bubble up to the highest levels of influence and policy. Governments spend valuable time and political capital banning plastic straws, but do little to incentivize more useful interventions, like heat pumps, or regulate the oil industry. Corporations are praised or criticized most loudly for their packaging. If we can't prioritize our individual efforts, it's unlikely that we'll apply effective pressure to those with more influence.

So of course, there's no harm in eliminating plastic straws from your routine. On its own, that would be great. But looking at the general conversation, I think we're being swept away by our performance of Green Theater and incurring some very high opportunity costs in the process.

Remaining Questions + Uncertainty

Because I've compiled a lot of sources, and because estimating carbon emissions amidst so much variation and change is inherently somewhat uncertain, it's possible that some of the values listed are incorrect. I've tried to document my sources and calculations thoroughly, and I'll try to keep them up to date as I learn more. But even if there's some disagreement about specifics, these figures demonstrate the huge variation in the costs and benefits of everything we do, and therefore the importance of better prioritization.

A few questions that I'd like to investigate separately:

- Are carbon offsets worth the money?

- What happens to my plastic recycling (in San Francisco)?

- Are organic crops better for the environment?

Footnotes

[1] Cousin to hygiene and security theater, Green Theater is the set of well intentioned but mostly ineffective climate change interventions.

[2] Plastic waste that's disposed of properly in developed countries will almost certainly end up recycled or in a landfill- not in the ocean. And because it takes so long to decompose, plastic in landfills won't release much CO2.

[3] Critics may point out that producing these appliances is itself a carbon intensive process, but they should earn back the upfront costs if they’re used for long enough and fueled with sufficiently clean electricity.

[4] In addition to cows, sheep and buffalo also produce methane in their digestion process (enteric fermentation), though there is promising research about a dietary supplement that could help significantly.

[5] There are some plausible critiques of this focus on beef. For one, land use change makes up a big portion of beef's emissions, but cattle in the US are often raised on land that couldn't naturally support a forest or even crops. It's not clear that statistics take this into account. Critics also point out that agriculture makes up just 9% of US emissions, compared to 25% globally. But this is because our transportation and industrial emissions are so high, not because our agriculture is particularly environmentally friendly. So, it's possible that diet changes are being mis-prioritized for some people or that the source of your beef (especially whether it's linked to deforestation) could significantly change the environmental costs. But overall, the concern about beef consumption in the developed world is probably justified.

[6] After more research, see "Remaining Questions"